A literary agent sells your book for you. More specifically, they know all the editors at all the publishing houses, big and small, who want to publish a book like yours. They maintain those relationships so that when the perfect book (yours!) comes up, they are a trusted source.

Agents are also up to date on the direction of the market, and they'll advise you on what to write next, or how to best revise your work to receive the right audience.

They'll also negotiate your deal, usually getting you a lot more money than you could have gotten on your own. An agent is your advocate, the person who is on your side. Most of the big publishing houses won't take your submission without an agent, and even smaller houses prefer agented manuscripts.

Now. How do you go about picking one?

Start with the big resources:

Query Tracker

Publisher's Marketplace

Agent Query

Compile a list of agents who are active, accepting submissions, and represent your category and genre. This list will be very long. Hundreds of names. Now you'll narrow them down based on your own personal criteria. Some of the more common criteria:

- Have they made a sale to a publishing house you know and respect in the last year?

- Are their current clients experiencing success?

- Do they respond in a reasonable amount of time? Even after you've been signed?

- Are they reputable?

Those answers can be found on sites like Preditors and Editors as well as the Absolute Write Water Cooler forums. Just google "absolute write <agent name>" and you'll be taken right to the page where everybody else is talking about this agent.

Once you narrow the list down once, you can go a little further based on your personal preferences. Some things to consider:

- How tech-savvy are they? Do they expect you to be the same?

- How communicative are they?

- Her personable are they?

- Do their reading tastes mirror your own?

To find this info, you'll need to dig deeper. Twitter, blogs, personal websites (most agents will maintain a blog or tumblr in addition to their agency's official website). Find interviews they've given. Most agents will get featured on Writer's Digest or even on smaller blogs and websites.

By this point, depending on how picky you are, you'll have a list that's somewhere between ten and a hundred names long, and it's time to start querying :)

This site is currently undergoing a major overhaul. We hope to have it improved and ready to rock your socks off soon. In the mean time, feel free to look around, but please know that more resources are coming every day and this is a work in progress. Thank you.

Wednesday, November 27, 2013

Tuesday, November 26, 2013

Queries: A Do and Don't List

When writing a query letter, DO:

- Use the same voice and tone of your novel. A funny, quirky query sets up expectations of a funny, quirky novel. Dark query, dark novel. Look at your adjectives and verbs in particular. They should show you the tone of your story. Try giving your query to someone who hasn't read your book and ask them to tell you what they expect based on the blurb.

- World build just a little. Enough that we understand it's a fantasy world or a contemporary one, but we don't need names of all the places, especially if they're weird.

- Use specific language. Look at this example:

- Clearly state your genre and category using universally accepted terminology. You didn't write a YA/Adult crossover romantic suspense horror fantasy. No. You didn't. Define your work.

When writing a query letter, DON'T:

- Give away the ending. The letter is supposed to entice people to read more. Find the climax of your story, and stop just before that point in telling the story in your query.

- Ask rhetorical questions. It's too easy for a busy agent to answer them flippantly, and your query then gets ignored.

- Use outliers as your comp titles. Do this exercise: List the first ten books you can think of in your genre and category. Ask a reader who is not a writer to do the same. Don't use any of those books. Twilight, Harry Potter, Eragon, Hunger Games, The Help, etc. Any of those books that "everybody" has read, any books that people say "I don't usually read, but I loved that book." are not good comp titles. They're too exceptional - the rules don't apply to them. The rules apply to you.

- Make predictions about your own success. This goes both ways. Don't predict that you'll be a mega-bestselling-genius, and don't predict that you'll be a bargain-bucket-dwelling-loser. Just don't mention it. Let your writing sell itself.

- Insult anybody. Ever. Not the agent, not yourself, not other writers. Never.

- LIE. Never. Not about anything. Don't lie about how many sales you've had or where you've published or the importance of your role in writing organizations. Don't lie about where you went to school and who you studied with. Don't lie about meeting an agent at a convention, don't lie about awards you've been given, or places you've been published. Don't lie. There are plenty of first time authors who get published without ever having any credentials.

- Use the same voice and tone of your novel. A funny, quirky query sets up expectations of a funny, quirky novel. Dark query, dark novel. Look at your adjectives and verbs in particular. They should show you the tone of your story. Try giving your query to someone who hasn't read your book and ask them to tell you what they expect based on the blurb.

- World build just a little. Enough that we understand it's a fantasy world or a contemporary one, but we don't need names of all the places, especially if they're weird.

- Use specific language. Look at this example:

When <character name> learns of an evil overlord threatening the safety of his world, he is determined to defeat him. After multiple narrows escapes, <character> learns of a prophecy that tells him he is The Chosen One and is the only person who can defeat the Dark Lord.Along the way, <character> meets some new friends, including a very pretty girl, and is sorely tempted by a mysteriously powerful object. Many of <character>’s friends fall or betray him, including his mentor.Finally, <character> faces the Dark Lord, the fate of everyone resting on his ill-prepared shoulders. Will he manage to escape yet again?What story is that? Try guessing the comments. I bet you'll be right, since it describes about a hundred different stories. Vague descriptions are useless.

- Clearly state your genre and category using universally accepted terminology. You didn't write a YA/Adult crossover romantic suspense horror fantasy. No. You didn't. Define your work.

When writing a query letter, DON'T:

- Give away the ending. The letter is supposed to entice people to read more. Find the climax of your story, and stop just before that point in telling the story in your query.

- Ask rhetorical questions. It's too easy for a busy agent to answer them flippantly, and your query then gets ignored.

- Use outliers as your comp titles. Do this exercise: List the first ten books you can think of in your genre and category. Ask a reader who is not a writer to do the same. Don't use any of those books. Twilight, Harry Potter, Eragon, Hunger Games, The Help, etc. Any of those books that "everybody" has read, any books that people say "I don't usually read, but I loved that book." are not good comp titles. They're too exceptional - the rules don't apply to them. The rules apply to you.

- Make predictions about your own success. This goes both ways. Don't predict that you'll be a mega-bestselling-genius, and don't predict that you'll be a bargain-bucket-dwelling-loser. Just don't mention it. Let your writing sell itself.

- Insult anybody. Ever. Not the agent, not yourself, not other writers. Never.

- LIE. Never. Not about anything. Don't lie about how many sales you've had or where you've published or the importance of your role in writing organizations. Don't lie about where you went to school and who you studied with. Don't lie about meeting an agent at a convention, don't lie about awards you've been given, or places you've been published. Don't lie. There are plenty of first time authors who get published without ever having any credentials.

Labels:

Gina Denny,

Querying,

Writing Fiction,

Writing Support

Monday, November 25, 2013

Query Letters

In order to get your book published, you need to write a query letter. You'll either write this to an agent or to a submissions editor, depending on the publishing path you're taking.

A query letter is a brief letter (less than one page long) that does the following things:

1. It introduces your book in a way that makes it sound enticing to read.

2. It demonstrates your ability to write coherently.

3. It introduces you as an author.

4. It provides agents and editors with a means of contacting you.

That's it. It does NOT:

1. Make predictions about how well a book will sell.

2. Insult anybody, ever.

3. Tell all about your life and your passions.

4. Do anything except for the four things listed above.

There are a few different formats on query letters, and every agent and editor will have a different bit of advice for you, but this is basically how it goes:

And that's it. That's the basics of it. Write the query letter first, and then go diving into some of the following resources to help you fix it. Why do it in that order? Because you can't fix something that isn't there.

Agent Query - How to Write a Good Query

Query Shark - A real, live agent takes real, live queries and tells you why they suck and how to fix them. Read the archives. This is why you need to have your letter written first. As you dig through the archives, you'll see things that you did. And you'll fix them, one by one. And then you'll do more things wrong. And you'll fix them.

The Girl with the Green Pen - a veteran slushpile reader will critique your query for free. Three times. And then if you pay her only $15, she'll fix it as many times as you need. Even a hundred. She's legit, too. I wrote a post on MMW about Taryn's Query Day: She read hundreds of query letters, critiqued them all, and tweeted the best bits of advice all day long.

Kristin Nelson also wrote a fantastic post about query letters.

A query letter is a brief letter (less than one page long) that does the following things:

1. It introduces your book in a way that makes it sound enticing to read.

2. It demonstrates your ability to write coherently.

3. It introduces you as an author.

4. It provides agents and editors with a means of contacting you.

That's it. It does NOT:

1. Make predictions about how well a book will sell.

2. Insult anybody, ever.

3. Tell all about your life and your passions.

4. Do anything except for the four things listed above.

There are a few different formats on query letters, and every agent and editor will have a different bit of advice for you, but this is basically how it goes:

Dear Agent's First and Last Name,

This is a brief blurb about my book. It is told in third person, present tense. It doesn't name too many characters or use too much world-building jargon, and it is clear and concise. It sounds a lot like the blurb on the back cover of a novel. In fact, many back-cover-blurbs have been lifted directly from query letters. This blurb should also match the tone and voice of your novel.

The blurb can be one or two paragraphs, but probably not three or more. You will introduce your main character (or both main characters if you're writing romance) and what their main goal and conflict is. You will not reveal the ending, but you will also not leave it with a rhetorical question. You will write in a normal font, of a normal size. You will use standard industry formatting.

This next paragraph will be about the book. The title will be in ALL CAPS. You will list the category, the genre, and the word count (rounded off to the nearest thousand and written like this: 95,000 words). You might mention that it's part of a series, but always emphasize that this title stands alone, regardless. If your agent or editor of choice specifically asks, this would be a good place to list comp titles.

The very last paragraph is about you. Your writing credentials, starting with the most relevant first. If you don't have writing credentials, you can either skip this or talk about your writing platform or social media presence, but do so briefly. There is not one agent who cares more about your twitter followers than they do about your book.

Thank you for your time and consideration (this is your only option here, do not vary from this),

Your First and Last Name

Phone

Website/Blog

And that's it. That's the basics of it. Write the query letter first, and then go diving into some of the following resources to help you fix it. Why do it in that order? Because you can't fix something that isn't there.

Agent Query - How to Write a Good Query

Query Shark - A real, live agent takes real, live queries and tells you why they suck and how to fix them. Read the archives. This is why you need to have your letter written first. As you dig through the archives, you'll see things that you did. And you'll fix them, one by one. And then you'll do more things wrong. And you'll fix them.

The Girl with the Green Pen - a veteran slushpile reader will critique your query for free. Three times. And then if you pay her only $15, she'll fix it as many times as you need. Even a hundred. She's legit, too. I wrote a post on MMW about Taryn's Query Day: She read hundreds of query letters, critiqued them all, and tweeted the best bits of advice all day long.

Kristin Nelson also wrote a fantastic post about query letters.

Labels:

Gina Denny,

Querying,

Writing Fiction,

Writing Support

Saturday, November 23, 2013

CPs and Betas - Why You Need Them.

You hear these terms: "CP" and "Beta" tossed around a lot, and if you're new to the writing world, they can be confusing. Let's define them first, then talk about how to find good ones.

CP = Critique Partner

This person is sometimes referred to as an "alpha reader." They read your work in the early drafts, they advise you on making big, sweeping changes. They are your support system when you need to cry, when you need to celebrate, and when you need to brainstorm.

My CPs get regular emails, asking questions about "Wait. What if I changed this, is that crazy?" By the time the book is ready to query, they've read it probably three or four times and they deserve all the love in the world. They need to think like a writer.

(Full disclosure: One of my CPs is not a writer - she's just the most perceptive and honest reader who has more patience than Mother Teresa)

This is also a two-way street. I read their stuff with the same amount of honesty, and I want to see them succeed as much as I want to succeed . These are the people who will read all my books, and I will read all of theirs.

Beta Reader

This person will read a near-ready version of your book. They're usually part of your target demographic (i.e. - if you write middle grade, at least some of your beta readers need to be twelve years old, if you write young adult, you'll need to find actual, living teenagers to read your book). If they aren't your target demographic, then they read extensively in your genre and category.

Beta readers will make inline notes, checking for typos and such, but that's not really their job. From your betas, you'll basically get a thumbs-up or a thumbs-down on the big stuff. Is the book any good? Do they like the characters? Why or why not? Does the world make sense? Things like that.

You'll still make at least one round of edits after your betas finish reading, and I know more than one author who has gone back and done full rewrites after the beta round.

Where do you find them?

They are all writers or readers, so you need to be places where writers and readers congregate. On the internet, that means twitter. In real life, it's writing groups and book clubs.

Twitter

Try people you talk to often, or just tweet "I need a CP/Beta for a <category> <genre> that's about <# of words>. Any takers?" People will answer. If they don't, go follow more people, get to know more people, and try again.

CP Seek

CP Seek is a website where you can find people who want need critique partners and are willing to trade manuscripts. I found two of my very favorite readers, who write some of my most very favorite kinds of books, on CP Seek. I also found three who didn't work out so great - not anybody's fault, we just weren't a good fit for each other.

How do you know if you're a good fit?

Ideally, you'll have similar reading tastes. If I met somebody who hated Harry Potter, loves to read Tolstoy, and just doesn't understand Star Wars... we are not going to be a good fit. And that's okay. There's a CP out there for everyone, and you don't need someone who is going to accidentally insult your work simply because it's not their style.

You should also read pretty heavily in each other's genres and categories. I write adult fantasy, but I also read a lot of YA science fiction and fantasy, so I understand the differences and why something works or doesn't in YA. I don't read MG well, and I don't do literary fiction. At all.

One reader got a hole of my manuscript and wanted me to slash 25-30K, basically cutting everything that wasn't main plot or dialog, and even that needed to be shortened in her opinion. She didn't read adult fantasy (the MS in question was under 100K, and well within industry standards for the genre and category), she read YA contemporary, which is very dialog heavy, and short on word count by comparison.

She's a very good writer. She's a good reader. For someone else. Don't put yourself in that position.

CP = Critique Partner

This person is sometimes referred to as an "alpha reader." They read your work in the early drafts, they advise you on making big, sweeping changes. They are your support system when you need to cry, when you need to celebrate, and when you need to brainstorm.

My CPs get regular emails, asking questions about "Wait. What if I changed this, is that crazy?" By the time the book is ready to query, they've read it probably three or four times and they deserve all the love in the world. They need to think like a writer.

(Full disclosure: One of my CPs is not a writer - she's just the most perceptive and honest reader who has more patience than Mother Teresa)

This is also a two-way street. I read their stuff with the same amount of honesty, and I want to see them succeed as much as I want to succeed . These are the people who will read all my books, and I will read all of theirs.

Beta Reader

This person will read a near-ready version of your book. They're usually part of your target demographic (i.e. - if you write middle grade, at least some of your beta readers need to be twelve years old, if you write young adult, you'll need to find actual, living teenagers to read your book). If they aren't your target demographic, then they read extensively in your genre and category.

Beta readers will make inline notes, checking for typos and such, but that's not really their job. From your betas, you'll basically get a thumbs-up or a thumbs-down on the big stuff. Is the book any good? Do they like the characters? Why or why not? Does the world make sense? Things like that.

You'll still make at least one round of edits after your betas finish reading, and I know more than one author who has gone back and done full rewrites after the beta round.

Where do you find them?

They are all writers or readers, so you need to be places where writers and readers congregate. On the internet, that means twitter. In real life, it's writing groups and book clubs.

Try people you talk to often, or just tweet "I need a CP/Beta for a <category> <genre> that's about <# of words>. Any takers?" People will answer. If they don't, go follow more people, get to know more people, and try again.

CP Seek

CP Seek is a website where you can find people who want need critique partners and are willing to trade manuscripts. I found two of my very favorite readers, who write some of my most very favorite kinds of books, on CP Seek. I also found three who didn't work out so great - not anybody's fault, we just weren't a good fit for each other.

How do you know if you're a good fit?

Ideally, you'll have similar reading tastes. If I met somebody who hated Harry Potter, loves to read Tolstoy, and just doesn't understand Star Wars... we are not going to be a good fit. And that's okay. There's a CP out there for everyone, and you don't need someone who is going to accidentally insult your work simply because it's not their style.

You should also read pretty heavily in each other's genres and categories. I write adult fantasy, but I also read a lot of YA science fiction and fantasy, so I understand the differences and why something works or doesn't in YA. I don't read MG well, and I don't do literary fiction. At all.

One reader got a hole of my manuscript and wanted me to slash 25-30K, basically cutting everything that wasn't main plot or dialog, and even that needed to be shortened in her opinion. She didn't read adult fantasy (the MS in question was under 100K, and well within industry standards for the genre and category), she read YA contemporary, which is very dialog heavy, and short on word count by comparison.

She's a very good writer. She's a good reader. For someone else. Don't put yourself in that position.

Friday, November 22, 2013

Plotting Tips

This is a compilation of the best plotting tips I can find out there on the web.

This is the idea that you start with something simple: a one-sentence description of your book. Then you expand on it: a single paragraph describing your story. Then you pull apart each one of those sentences and turn them into their own paragraphs, and so on and so forth.

|

| Expound on each point, and then expound on those - a snowflake |

This is most often attributed to Dan Wells and is the idea that every story really only needs seven things: A hook, two plot turns, two "pinches", a midpoint, and a resolution. This one is particularly useful if you write character-driven stories, as the hook and the resolution are mirror-images of each other, and that's much easier to do with a character arc than with an actual physical story.

His whole powerpoint for this presentation is looooooong, but some of the summarizing blog posts are easier to get through, and his video presentation of it is excellent.

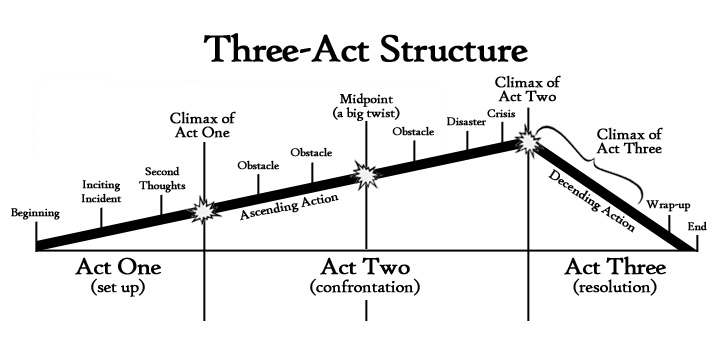

This is the basic, classic method of plotting a novel. Three acts, one main arc of the story.

This follows the "Happily Ever After" format and pacing that makes Hollywood movies so successful. This is particularly useful with middle grade and young adult fiction, which both tend to be a little shorter and faster-paced (thus lining up with a movie format nicely).

If none of those work for you, Chuck Wendig (if you aren't reading his blog on a regular basis, you need to) wrote an excellent post on twenty-five plotting methods.

Labels:

Gina Denny,

Plotting,

Writing Fiction,

Writing Support

Thursday, November 21, 2013

In Defense of Pantsing

I try to be a good plotter, I really do.

But it just never works out that way.

Pantsing, if you don't already know, is a writerly term for "flying by the seat of your pants" while writing.

Some writers just sit down and do a stream-of-consciousness thing until they find a story or a character.

Others (like me) start with a vague idea of where the story needs to go but have no actual idea on how that's going to happen. I tried plotting for my NaNoWriMo effort this year, and I used Dan Wells' 7 Point Plot System. I really thought that was enough.

Yeah. Ten gets it.

It's not enough. 7 Points did give me an emotional framework for the novel, and that helped tremendously, but it still wasn't enough for the physical plot of the thing. And so I winged it. (wung it?)

The first scene I had planned turned out to be really dull and so I skipped forward and started writing someplace else. About two-thirds of the way through the book, I said, "OOH! I need to go back to the beginning and add in a scene about THIS." I went back... and that was basically how I started. It was different than my "plan", but in the end it was better for the characters and better for the story. I just didn't know it yet.

The upside of pantsing:

You get to meet your story and fall in love with your characters as if you're the reader.

The downside:

You usually have a hot mess to deal with and you'll do a lot more work in revisions than a plotter.

The choice is yours.

But it just never works out that way.

Pantsing, if you don't already know, is a writerly term for "flying by the seat of your pants" while writing.

Some writers just sit down and do a stream-of-consciousness thing until they find a story or a character.

Others (like me) start with a vague idea of where the story needs to go but have no actual idea on how that's going to happen. I tried plotting for my NaNoWriMo effort this year, and I used Dan Wells' 7 Point Plot System. I really thought that was enough.

Yeah. Ten gets it.

It's not enough. 7 Points did give me an emotional framework for the novel, and that helped tremendously, but it still wasn't enough for the physical plot of the thing. And so I winged it. (wung it?)

The first scene I had planned turned out to be really dull and so I skipped forward and started writing someplace else. About two-thirds of the way through the book, I said, "OOH! I need to go back to the beginning and add in a scene about THIS." I went back... and that was basically how I started. It was different than my "plan", but in the end it was better for the characters and better for the story. I just didn't know it yet.

The upside of pantsing:

You get to meet your story and fall in love with your characters as if you're the reader.

The downside:

You usually have a hot mess to deal with and you'll do a lot more work in revisions than a plotter.

The choice is yours.

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

The Purpose of Writing

Writing to

relay information, whether it’s been in a letter or book has been going on for

centuries, but what about writing for our own self-fulfillment?

Diaries, journals, and personal manifestations have been for the purpose of the author’s own enjoyment, otherwise why would he or she continue to write in them? If they didn’t find that they were getting anything out of it?

Yes, those works are beneficial to the descendants of the author, but how does it help the author as he or she is in the process of writing it? I know in my own experience that while I’ve been blogging about writing, it has been more about discovering who I am as an author and a wife and a mother.

This process has come to help me understand that what I’m writing is always for my benefit regardless of getting published. An author friend once told me that she writes what she enjoys and she is beyond grateful that hundreds of readers agree with her. I remember receiving this answer when I shared with her that I thought my writing was funny and what if others didn’t see it that way. It was then that I realized I’m doing this for me because I enjoy writing.

I’ve always loved making up stories, dreaming up my own characters and acting them out on paper. If none of my stories get published, I have learned something about myself and that is more important to me than the potential celebrity or wealth that may follow.

I write to know myself better.

Diaries, journals, and personal manifestations have been for the purpose of the author’s own enjoyment, otherwise why would he or she continue to write in them? If they didn’t find that they were getting anything out of it?

Yes, those works are beneficial to the descendants of the author, but how does it help the author as he or she is in the process of writing it? I know in my own experience that while I’ve been blogging about writing, it has been more about discovering who I am as an author and a wife and a mother.

This process has come to help me understand that what I’m writing is always for my benefit regardless of getting published. An author friend once told me that she writes what she enjoys and she is beyond grateful that hundreds of readers agree with her. I remember receiving this answer when I shared with her that I thought my writing was funny and what if others didn’t see it that way. It was then that I realized I’m doing this for me because I enjoy writing.

I’ve always loved making up stories, dreaming up my own characters and acting them out on paper. If none of my stories get published, I have learned something about myself and that is more important to me than the potential celebrity or wealth that may follow.

I write to know myself better.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)